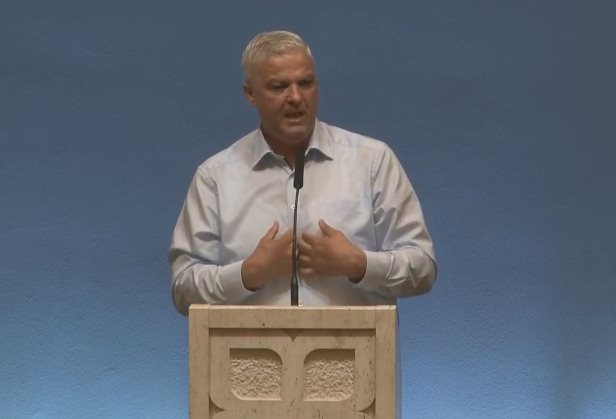

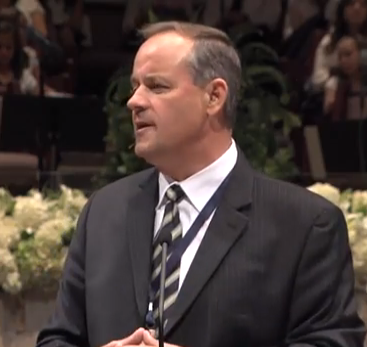

Peter Williams is the CEO of Tyndale House Cambridge and a lecturer on Hebrew language at the University of Cambridge

Peter Williams – Moral Objections To The Bible

16 nov. 2015 Comentarii închise la Peter Williams – Moral Objections To The Bible

in Apologetics, BIBLE Etichete:Moral Objections To The Bible, Peter Williams

Peter Williams – Historical Evidence For The Christian Faith – The Moody Church

15 nov. 2015 Comentarii închise la Peter Williams – Historical Evidence For The Christian Faith – The Moody Church

in Apologetics Etichete:Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith, Peter Williams, The Moody Church

Moral Attacks on the Old Testament – Peter Williams

01 apr. 2015 Comentarii închise la Moral Attacks on the Old Testament – Peter Williams

in Apologetics, Archaeology, BIBLE, Jesus Christ, Word of God Etichete:Moral Attacks on the Old Testament, Peter Williams

http://nphx.org – Lecture by Peter Williams who is the current Warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK. This video is part of the North Phoenix Baptist Church Apologetics Conference 2015 playlist:https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

http://nphx.org – Lecture by Peter Williams who is the current Warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK. This video is part of the North Phoenix Baptist Church Apologetics Conference 2015 playlist:https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Downloads the notes for this lecture here:

http://cpmassets.com/download.php?fil…

How You Can Be Ready to Witness (Session 5 of 5) Peter Williams

30 ian. 2015 Un comentariu

in Apologetics Etichete:How You Can Be Ready to Witness, Peter Williams

- See Part 1 here – Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith (Session 1 of 5) Peter Williams (Tyndale House)

- Part 2 – The Ancient Manuscripts and the Text of the New Testament (Session 2 of 5)

- Part 3 – Moral Attacks on the Old Testament (Session 3 of 5) Peter Williams

- Part 4 – What Did the Church Do to the Bible?

How You Can Be Ready to Witness (Session 5 of 5) from North Phoenix Baptist Church on Vimeo.

Moral Attacks on the Old Testament (Session 3 of 5) Peter Williams

28 ian. 2015 Un comentariu

in Apologetics Etichete:Moral Attacks on the Old Testament, Peter Williams

- See Part 1 here – Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith (Session 1 of 5) Peter Williams (Tyndale House)

- Part 2 – The Ancient Manuscripts and the Text of the New Testament (Session 2 of 5)

North Phoenix Baptist Church Apologetics Conference 2015.

Dr. Peter Williams who is the current Warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK.

Moral Attacks on the Old Testament (Session 3 of 5) from North Phoenix Baptist Church on Vimeo.

Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith (Session 1 of 5) Peter Williams (Tyndale House)

26 ian. 2015 Un comentariu

in Apologetics Etichete:Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith, Peter Williams

North Phoenix Baptist Church Apologetics Conference 2015.

Dr. Peter Williams who is the current Warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK.

Historical Evidence For the Christian Faith (Session 1 of 5) from North Phoenix Baptist Church on Vimeo.

A Conversation With Peter Williams, Ph.D. of Tyndale House

02 aug. 2014 Un comentariu

in Apologetics, BIBLE Etichete:Conversation, Peter Williams, Ph.D., Tyndale House

„One of the things we’ve got to do is not be scared by that [future] but to dig really deep roots into the Scriptures to find out what exactly the Scripture teaches – not to try to adapt it to make it more trendy and palatable, but to think what exactly it’s teaching us with the questions we are facing today.”

Peter Williams, Ph.D. is a well-known apologist and author. He is the Warden at Tyndale House, Cambridge in the UK. In this interview Peter discusses Church oneness, finding our roots in Scripture, being witnesses of Christ, his thoughts about why Jesus was a carpenter, and much more.

A Conversation With Peter Williams, Ph.D. from Future of the Church on Vimeo.

Did God really say? VIDEO with full transcript

26 sept. 2013 Comentarii închise la Did God really say? VIDEO with full transcript

in Apologetics, Jesus Christ, Trinity, Uncategorized, Word of God Etichete:Al Mohler, Bible, Biblical inerrancy, Christ and the Bible, Did God really say?, Dr Simon Gathercole (Cambridge England), Francis A Schaeffer, Fuller Theological Seminary, Fundamentalism and the word of God, He is there and He is not silent, inerrancy, J Gresham Machen, J.I.Packer, Jesus, John D. Woodbridge, John Piper, John Wenham, Ligon Duncan, Mark Dever, Ned B Stonehouse, New Testament, Peter Enns, Peter Williams, Scripture and Truth, Together for the Gospel, Together for the Gospel 2012

An essential, highly interesting affirmation by the panel of the belief on biblical inerrancy from the Together for the Gospel Conference 2012, led by Mark Dever, Pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington D.C. Besides the great panel discussion, there are also a few book recommendations (linked to Amazon, just click on title or photo) and lots of links to search peripheral issues as they relate to the inerrancy debate. This page will be added to the (permanent) apologetics page.

An essential, highly interesting affirmation by the panel of the belief on biblical inerrancy from the Together for the Gospel Conference 2012, led by Mark Dever, Pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington D.C. Besides the great panel discussion, there are also a few book recommendations (linked to Amazon, just click on title or photo) and lots of links to search peripheral issues as they relate to the inerrancy debate. This page will be added to the (permanent) apologetics page.

photo from T4G website – http://t4g.org/resources/photos/

- We affirm that the sole (final) authority for the Church is the Bible, verbally inspired, inerrant, infallible and totally sufficient and trustworthy. We deny that the Bible is a mere witness to the divine revelation or that any portion of Scripture is marked by error or by effects of human sinfulness.

- We affirm that the authority and the sufficiently of Scripture extends to the entire Bible and that therefore the Bible is our final authority for all doctrine and practice. We deny that any portion of the Bible should be used in an effort to deny the truthfulness or trustworthiness of any other portion. We further deny any effort to identify a canon within the canon or for example to set the words of Jesus against the words of Paul.

- We affirm that truth ever remains a central issue for the Church and that the Church must resist the allure of pragmatism and post modern conceptions of truths as substitutes for obedience to the comprehensive truth claims of Scripture. We deny that truth is merely a product of social construction or that the truth of the Gospel can be expressed or grounded in anything less than total confidence in the veracity of the Bible, the historicity of the biblical events and the ability of language to convey understandable truth in sentence form. We further deny that the church can establish its ministry on a foundation of pragmatism, current marketing techniques or contemporary cultural fashions.

Is inerrancy something new? Short answer „NO!”

Minute 4 – Dever addresses the charge that „inerrancy” is a „new thing” or just a „reformation doctrine?”.

John Piper responds:.In 1971 Fuller Theological Seminary took the Word out. I read what was happening in Germany. It blew me away. I did not see it coming. So it may have been there, but the teachers that I loved and had influenced me most didn’t talk that way and didn’t give me indication that it would be going that way. I was never able to make any sense out of the distinctions between infallible and inerrant.

John Piper responds:.In 1971 Fuller Theological Seminary took the Word out. I read what was happening in Germany. It blew me away. I did not see it coming. So it may have been there, but the teachers that I loved and had influenced me most didn’t talk that way and didn’t give me indication that it would be going that way. I was never able to make any sense out of the distinctions between infallible and inerrant. - Dr Simon Gathercole – teaches New Testament at Cambridge, in England. One of the clearest figures to express a doctrine of inerrancy was St. Augustine and it came up for him in conversation with the Manichaeans where he made it very clear that there were no contradictions in Scripture , that if you do find what looks like a mistake in Scripture, it is either a result of a problem with the translation, a problem in the text, a particular manuscript or scribal error or that you have misunderstood it. So Augustine is an example of someone who was very clear on inerrancy.

- Ligon Duncan – there is a consistent witness across Christian history to the Bible’s sole, final authority and its inspiration and inerrancy.

Peter Williams – (undergraduate studies at Cambridge) „I believe it is fully authoritative, inerrant, inspired by God’ I think I’d want to add more words, I want to say: It’s basically clear, it’s sufficient, it’s historical. People can take a word like „inerrant” and leech it (by saying) – „I agree with the notion that Scripture is entirely true, but then they try and weaken it in other ways and I think that’s happening particularly because a lot of people, at least in this country are signing an inerrancy statement for their paycheck (which sometimes happens; they redefine inerrancy). There are many reasons to believe in inerrancy, but I think when you believe in verbal inspiration (i.e.) that God gave words and you believe in God’s trustworthiness, that He has a true character and you want to have a relationship with God, then it is inescapable logically to come to a view of Scriptural inerrancy. If you believe that God has given words, I don’t see how you can break that and say, „Well, He gives words and they are sometimes full of errors”, without actually questioning God’s trustworthiness Himself.

Peter Williams – (undergraduate studies at Cambridge) „I believe it is fully authoritative, inerrant, inspired by God’ I think I’d want to add more words, I want to say: It’s basically clear, it’s sufficient, it’s historical. People can take a word like „inerrant” and leech it (by saying) – „I agree with the notion that Scripture is entirely true, but then they try and weaken it in other ways and I think that’s happening particularly because a lot of people, at least in this country are signing an inerrancy statement for their paycheck (which sometimes happens; they redefine inerrancy). There are many reasons to believe in inerrancy, but I think when you believe in verbal inspiration (i.e.) that God gave words and you believe in God’s trustworthiness, that He has a true character and you want to have a relationship with God, then it is inescapable logically to come to a view of Scriptural inerrancy. If you believe that God has given words, I don’t see how you can break that and say, „Well, He gives words and they are sometimes full of errors”, without actually questioning God’s trustworthiness Himself.

The 3 roots/trajectories on how inerrancy is denied

Al Mohler (11 min mark) Why wouldn’t anyone believe in this? (This question) leads to a principle of interpreting church history, which often surprises people when you first hear it, and that is that „heresy precedes orthodoxy„. That doesn’t mean that the false precedes the true. It does mean that the codification, or confession of the faith is often in the face of, is a response to heresy or that which is sub biblical or sub orthodox. So, in 325 AD you have a statement made by the Council of Nicaea, that wasn’t necessary until Arius denied that the father and the Son are of the same substance. And when it comes to inerrancy, the first thing is that this is God’s word, God is totally true, so all the attributes of Scripture seem to come, and yet Augustine has to respond to the Manichaeans and we have to respond to contemporary denials of the total truthfulness of Scripture. I think there are 3 roots, or 3 trajectories in which that comes:

Al Mohler (11 min mark) Why wouldn’t anyone believe in this? (This question) leads to a principle of interpreting church history, which often surprises people when you first hear it, and that is that „heresy precedes orthodoxy„. That doesn’t mean that the false precedes the true. It does mean that the codification, or confession of the faith is often in the face of, is a response to heresy or that which is sub biblical or sub orthodox. So, in 325 AD you have a statement made by the Council of Nicaea, that wasn’t necessary until Arius denied that the father and the Son are of the same substance. And when it comes to inerrancy, the first thing is that this is God’s word, God is totally true, so all the attributes of Scripture seem to come, and yet Augustine has to respond to the Manichaeans and we have to respond to contemporary denials of the total truthfulness of Scripture. I think there are 3 roots, or 3 trajectories in which that comes:

- The first is ideological and this is basically the external critique of biblical inerrancy. It comes from new atheists, of course if you don’t believe in God, you don’t believe there could possibly be a word of God; if you don’t believe in supernatural revelation as a possibility, or even recently, if you don’t believe in words as units of meaning; that are capable of conveying truth, there are various rules of philosophy and literary interpretation that have lost all confidence in words. They have to use words to explain how little confidence they have in them any longer; it’s part of the whole conundrum, but nevertheless, it is an ideological assault and so a good bit of what you will read simply says: „Inerrancy is an impossibility” and it will move on. But, it is not the major issue of our concern, there are two other trajectories.

- Another trajectory is apologetic. This is where you have evangelicals who say: This is an embarrassment. To claim inerrancy is to over claim the text, it is an impediment to our intellectual credibility and so you have people who would pose to be within the evangelical movement who will say, as Kenton Sparks in a recent book said, „This is the intellectual doom,” to paraphrase him, because it makes us continually defend the truthfulness of every passage in a text and that is leading modern people to have huge intellectual obstacles to receiving the main message in the text, which is the Gospel of Jesus Christ. So you have various forms of this kind of apologetic argument; it’s the same argument as people who come along and say you can’t talk about the Bible’s teaching on sexuality; that’s presenting too much of an obstacle for contemporary people to come to Christ. Ot, you can’t deny the theory of evolution, it’s metanarrative because that creates too much of an impediment for people to come to Christ. And so, you have websites today and people arguing that inerrancy is just an obstacle, it’s a theological construct that’s doing more damage than good.

- The third trajectory, or the third root you can look at this is moral, in which case you have people say that if we’re committed to total truthfulness of Scripture, then we’re committed to text which reveal God as acting in immoral ways; God’s people sanctioning immoral acts, and what you have is people who will say, „Look, we have the capacity as human beings to judge God, and thus we’re gonna go to the conquest of Canaan or we’re gonna go to the way God deals with any individual in either Testament of the canon and say that that’s immoral. If you’re gonna try and impose a human standard of morality, like the late atheist, Christopher Hitchens, if you read the Bible honestly you’re gonna find texts that are gonna cause you all kinds of difficulty and by the way, one of the things Christopher Hitchens did very well for us was to say, „He can understand theists who believe in the inerrancy of Scripture and he can understand atheists who don’t believe it’s possible, what he didn’t understand were people who tried to pose in the middle.

Dr Simon Gathercole – The central plank for me in the doctrine of inerrancy, and that is that it was Jesus’ view of Scripture and I think the 2 other points that were mentioned are really significant. The sort of dogmatic logic of what Scripture says, God says and therefore because of the character of God, Scripture is without error. Also, it’s the continuous testimony of the Church. I would recommend everyone read John Woodbridge’s book Biblical Authority: A Critique of the Rogers/McKim Proposal even though the debate is now different, but there’s a lot to learn there. But, if you just look at the way Jesus treats Scripture, what He says about Scripture, „Your word is truth”, „Scripture cannot be broken”, the way He refers to Adam, the way He refers to Elijah and Elisha, all the figures of the Old Testament, the way He responds to Satan: „It’s written, and every word is proceeding from the mouth of God.” That has to be the real cornerstone for our doctrine of inerrancy and it means that it’s an imperative of discipleship for us, that it’s a matter of following Jesus. (Also recommends „Christ and the Bible” by John Wenham)

Dr Simon Gathercole – The central plank for me in the doctrine of inerrancy, and that is that it was Jesus’ view of Scripture and I think the 2 other points that were mentioned are really significant. The sort of dogmatic logic of what Scripture says, God says and therefore because of the character of God, Scripture is without error. Also, it’s the continuous testimony of the Church. I would recommend everyone read John Woodbridge’s book Biblical Authority: A Critique of the Rogers/McKim Proposal even though the debate is now different, but there’s a lot to learn there. But, if you just look at the way Jesus treats Scripture, what He says about Scripture, „Your word is truth”, „Scripture cannot be broken”, the way He refers to Adam, the way He refers to Elijah and Elisha, all the figures of the Old Testament, the way He responds to Satan: „It’s written, and every word is proceeding from the mouth of God.” That has to be the real cornerstone for our doctrine of inerrancy and it means that it’s an imperative of discipleship for us, that it’s a matter of following Jesus. (Also recommends „Christ and the Bible” by John Wenham)- Peter Williams – If heresy precedes orthodoxy then I think that apologetics precedes heresy, as in most heresy begins as apologetics movement. And, I say that as someone who is involved in apologetics and likes it. Liberal theology is an attempt to rescue Christianity from deep embarrassment and that’s how a lot of these things begin and those of us that are involved in apologetics need to be quite careful about that, because it can lead to error. The way people get seduced sometime into abandoning Scriptural authority is when they become persuaded that, that thing which adheres most to their dreams and their aspirations and start to believe „that more people will come to Christ if I just water this down somewhat”. Sometime people become persuaded in theological education that they are being more faithful to the text if they read it in a way that is contrary to another text. When people are being brought up in a Chirstian context, to value the authority of the Bible, it appeals and they become persuaded that the most honest reading of the text is to read it so it contradicts to another one.

- Al Mohler – Liberal theology is a succession of rescue attempts for the reputation of Christianity and to just give an example of what Peter is talking about: You have Rudolph Bultmann, who in one of his books says people who use electric lights don’t believe in a supernatural universe. So, in other words, if you’re gonna reach modern people we’re gonna have to bring christianity into intellectual credibility with the modern world. A lot of the things you see being claimed right now are as old as the heretics that the church fathers faced and certainly in terms of protestant liberalism and what the church has faced in over 100 years.

Ligon Duncan – Another example in modern liberalism is Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher. Schleiermacher was offended by the doctrine of the penal substitutionary atonement of Christ and the uniqueness of Christ. And he looked out at Germany and he said: German intellectuals are rejecting Christianity in droves, they’re impacted by the enlightenment and the message of Christianity must change if we are going to be able to capture this generation for christianity. It wasn’t as if he was sitting around inventing to destroy christianity, but in fact he did that with apologetic missionary motives in reaching his culture and so liberalism’s fundamental premise is that the message must change if christianity is going to survive and effectively engage the culture.

Ligon Duncan – Another example in modern liberalism is Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher. Schleiermacher was offended by the doctrine of the penal substitutionary atonement of Christ and the uniqueness of Christ. And he looked out at Germany and he said: German intellectuals are rejecting Christianity in droves, they’re impacted by the enlightenment and the message of Christianity must change if we are going to be able to capture this generation for christianity. It wasn’t as if he was sitting around inventing to destroy christianity, but in fact he did that with apologetic missionary motives in reaching his culture and so liberalism’s fundamental premise is that the message must change if christianity is going to survive and effectively engage the culture.- Peter Williams -It’s going right back to Marcion in the second century. Marcion is deeply embarrassed by the Old Testament, by the Jewishness of Jesus. He, as an apologist thinks that he can commend christianity far better by ditching those things. So, that’s why becoming an apologist, led straight to the heresy.

John Piper (minute 20 mark) Mark Dever asks why JP concluded that inerrancy was true: There are layers to that like- My momma told me it was true. That’s one layer. „..remember those from whom you’ve learned the faith” (2 Timothy 3:14), that’s an argument in the Bible. Second layer would be: God made me see it. That’s the deepest layer and I do believe I couldn’t believe the Bible is untrue, if I tried because I am just taken by Him, for it. I believe that’s the deepest reason. You can’t persuade anybody with that and so, up above those layers are the layers of experience, of encounter with the text and I think that at one level the Bible, as C.S.Lewis said: „You believe in it as you believe in the sun, not only because you see it, but you see everything else by it”. I asked my professor in Germany one time, „Why do you believe the Bible? And he said: Because it makes sense out of the world for me. Year after year, after year you live in the book and you deal with the world and it brings coherence to evil and good and sorrow and loss. And there’s one other level I would mention: Liar, lunatic, Lord argument in the Gospels works for me in Paul: Liar, lunatic or faithful apostle because I think I know Paul better than I know anybody in the Bible. Luke wrote most quantitatively, but he’s writing narrative. But with Paul, if you read these 13 letters hundreds of times, you know this man. Either he’s stupid, I mean insane, or liar, or a very wise, deep, credible, thoughtful person. So, when I put Paul against any liberal scholar in any German university that I ever met, they don’t even come close. So, I have never, frankly, been tested very much by the devil or whoever to say, „This wise, liberal, offering his arguments…” I read Paul and I say, „I don’t think so”. This man is extraordinary, he’s smart, he’s rational. He’s been in the 3rd, 7th heaven and he is careful about what he is saying. So, that whole argument „Liar, lunatic, Lord – works for me with Jesus and it works powerfully for me for Paul and moreover once you’ve got Paul speaking, self authenticating, irresistible, world view shaping truth, then as you move out from Jesus and Paul, the others just start to shine with confirming evidences. Just a few ayers, there are others. Dever prompts John to give one more. JP: Why are you married after 43 years? How do you endure losses? really, where does your strength come from? You will know the truth and the truth will set you free. Free from pornography and free from divorce, free from depressions that just undo you. How do you find your way into marriage over and over and out of depression and away form the internet? How does that happen? It happens by the power of this incredible book. Dever: For people who haven’t had time to accumulate all those layers, anything you would tell them to read? Piper: Back when the inerrancy council was red hot „Scripture and truth” edited by Grudem and

John Piper (minute 20 mark) Mark Dever asks why JP concluded that inerrancy was true: There are layers to that like- My momma told me it was true. That’s one layer. „..remember those from whom you’ve learned the faith” (2 Timothy 3:14), that’s an argument in the Bible. Second layer would be: God made me see it. That’s the deepest layer and I do believe I couldn’t believe the Bible is untrue, if I tried because I am just taken by Him, for it. I believe that’s the deepest reason. You can’t persuade anybody with that and so, up above those layers are the layers of experience, of encounter with the text and I think that at one level the Bible, as C.S.Lewis said: „You believe in it as you believe in the sun, not only because you see it, but you see everything else by it”. I asked my professor in Germany one time, „Why do you believe the Bible? And he said: Because it makes sense out of the world for me. Year after year, after year you live in the book and you deal with the world and it brings coherence to evil and good and sorrow and loss. And there’s one other level I would mention: Liar, lunatic, Lord argument in the Gospels works for me in Paul: Liar, lunatic or faithful apostle because I think I know Paul better than I know anybody in the Bible. Luke wrote most quantitatively, but he’s writing narrative. But with Paul, if you read these 13 letters hundreds of times, you know this man. Either he’s stupid, I mean insane, or liar, or a very wise, deep, credible, thoughtful person. So, when I put Paul against any liberal scholar in any German university that I ever met, they don’t even come close. So, I have never, frankly, been tested very much by the devil or whoever to say, „This wise, liberal, offering his arguments…” I read Paul and I say, „I don’t think so”. This man is extraordinary, he’s smart, he’s rational. He’s been in the 3rd, 7th heaven and he is careful about what he is saying. So, that whole argument „Liar, lunatic, Lord – works for me with Jesus and it works powerfully for me for Paul and moreover once you’ve got Paul speaking, self authenticating, irresistible, world view shaping truth, then as you move out from Jesus and Paul, the others just start to shine with confirming evidences. Just a few ayers, there are others. Dever prompts John to give one more. JP: Why are you married after 43 years? How do you endure losses? really, where does your strength come from? You will know the truth and the truth will set you free. Free from pornography and free from divorce, free from depressions that just undo you. How do you find your way into marriage over and over and out of depression and away form the internet? How does that happen? It happens by the power of this incredible book. Dever: For people who haven’t had time to accumulate all those layers, anything you would tell them to read? Piper: Back when the inerrancy council was red hot „Scripture and truth” edited by Grudem andMark Dever recommends J. I. Packer’s „Fundamentalism and the Word of God”.

- Al Mohler – The problem is how few of our confessional statements are clear on this in the first place. So one of our evangelical liabilities is that too much has been assumed under an article of Scripture without specifying language, with inerrancy being one of those necessary attributes of Scripture confirmed. You do find people today, some lamentably who are trying to claim that you can still use the word, while basically eviscerating it, emptying it of meaning. So you have historical denials, in particular, you have someone who says that a text… and „The Chicago Statement on Inerrancy” makes it very clear, our affirmations and denials are actually patterned after the International Council of Biblical Inerrancy, which was itself patterned after previous statements in which there were not only affirmations, but clear denials. So, when you look to that statement, you’ll see that there’s the version of what inerrancy means and that means „This is not true”. So, you have clear denials. One of the affirmations is: Scripture has different forms of literature, but the denial is that you can legitimately dehistoricize an historical text. So, in other words, everything in Scripture reveals, including every historical claim is true. You find some people saying: „Well, you can affirm the truthfulness of the text without the historicity of the text. You can’t do that. You have people who are now using genre criticism, various forms to say: This is a type of literature. My favorite of these lamentable arguments is the one that says: This is the kind of text to which the issue of inerrancy does not apply. In other words: I don’t like it. But, what they mean is: I am not making a truth claim. If I am not making a truth claim… that’s ridiculous, but you find these kinds of nuances going on. You also find very clear, points of friction. So, let’s give an example of points of friction: Do we have to believe in the historicity of the first eleven chapters of the book of Genesis? What Pete said about apologetics, that puts us over, against a dominant, intellectual system that establishes what is called credibility in the secular academy. Those evangelicals who feel intellectually accountable to that, are trying to say, „There has to be some other way then, of dealing with Genesis 1 through 11 and that’s where you have now the ultimate friction point, with coming, for instance, the historical Adam and an historical fall and now you’re finding people who are trying to say, „Okay, there is no historical claim in Genesis 1 through 3, but I still believe in an historical Adam because I am just going to pull him out of the air and pop him down and say, „I still believe in an historical Adam (but) I am not going to root it in the historical nature of the text, but I need him because Paul believed in him. And then, you have people who have websites today, someone like Peter Enns, who used to teach at an institution which required inerrancy, but no longer teaches there, who says, „Clearly, Paul did believe in inerrancy, but, Paul was wrong”. And so, now you not only have the denial of inerrancy of the historicity of Genesis 1 through 3, you have Paul now, in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 being said, „Well now, inerrancy for him means ‘he was speaking truthfully, as inspired by God, but limited to the world view that was accessible and available to him at the time’. That is not what Jesus believed about Scripture. That is not what the church must believe about Scripture. I never came close to not believing in the inerrancy of Scripture. I came close to believing that there could be other legitimate ways of describing the total authority and truthfulness of the text and especially in context of fierce denominational controversy, I thought there must be room for finding it somewhere else and some people even mentioned here were correctives. For example J.I. Packer’s Fundamentals of God, was the bomb that landed in the playground. That little experiment just doesn’t happen; you take that out, it simply won’t work. At about the time that you (Mark Dever) and I really became friends, we were looking at how you came from an evangelical background where those issues have been discussed for 20 years before they did explode in the Southern Baptist Convention. My denomination had to learn this lesson a little bit late and at great cost.

- Mark Dever– leaving the denominational stuff aside, you (Mohler) as a Christian, you found an intuitive, like John is talking about, an intuitive faith in Scripture.

Al Mohler– Well, it was intuitive, but I also had intellectual guardrails. My earliest, explicit theological formation was when apologetics hit me as a crisis as a teenager and I was led directly into the influence of Francis Schaeffer. And the book that most influenced me as a teenager in high school, holding on to the faith as against a very secular environment was his book based on lectures at Wheaton „He is there and He is not silent”, and I would point to that as the 5 or 10 books that most shaped my thinking, because Schaeffer’s logic in his lectures is really clear: „If there is a God, who doesn’t exist, we’re doomed. If there’s a God who does exist, but doesn’t speak, we’re just as doomed. If there is a God who does exist and He does speak, then salvation is in the speech. And so that was one of the guard rails in my life and being raised in a Gospel church that preached the word of God and just assumed that when you say „It’s the word of God”, it means all this.

Al Mohler– Well, it was intuitive, but I also had intellectual guardrails. My earliest, explicit theological formation was when apologetics hit me as a crisis as a teenager and I was led directly into the influence of Francis Schaeffer. And the book that most influenced me as a teenager in high school, holding on to the faith as against a very secular environment was his book based on lectures at Wheaton „He is there and He is not silent”, and I would point to that as the 5 or 10 books that most shaped my thinking, because Schaeffer’s logic in his lectures is really clear: „If there is a God, who doesn’t exist, we’re doomed. If there’s a God who does exist, but doesn’t speak, we’re just as doomed. If there is a God who does exist and He does speak, then salvation is in the speech. And so that was one of the guard rails in my life and being raised in a Gospel church that preached the word of God and just assumed that when you say „It’s the word of God”, it means all this.- Ligon Duncan – I didn’t have faith challenges as a teenager that Al did, but I was reading a lot of that apologetic literature and this was being talked about by evangelicals and the Ligonier statement on Scripture had come out in 1973, the ICBI Chicago Statement came out in 1978. Those are my teenage years. This is a conversation in the conservative corner of evangelicalism, in which I was reared. I had a good pastor that was happy to have me ask him questions about this when I was troubled with something I could ask him, he was on the board at Westminster Theological Seminary. When I went to Edinburgh (Scotland for PhD) I already had a solid education in the doctrine of Scripture at Covenant Seminary. But when I went to Edinburgh , James Barr’s book „Fundamentalism” had just come out and I read it. I have more writings in the margins of the text in this book. I was arguing with him relentlessly in this book.

- Mark Dever – This was an attack on J.I. Packer’s book and other kinds of statements of faith and Scripture.

Ligon Duncan – At that point I thought this would be some kind of hot topic. I had read some Barr in seminary, mostly semantics of biblical language and other things like that, in which, hopefully he is going after some bad stuff, but, I decided that when that book came out that I needed to read everything that Barr had ever written because of the potential influence on scholars. I was doing patristics at Edinburgh and so this wasn’t something that was part of my reading for work, it was just something I needed to do on the side and so I did. It was the most soul killing 6 months that I have ever spent. It was very disturbing. And several things helped me: One is a professor who had already thought through all of these issues. I went to another professor, and as we sat down he said, „You need to know, I have walked through all of these issues long ago and I’m happy to walk with you through them now. That was an enormous intellectual and theological resource to me. But then, it was the reality of Christ and the Gospel and the lives of believers that didn’t even know that they were ministering to me because that person could not be the way he or she is if there wasn’t a Holy Spirit indwelling Christ in us. I was also reading Ned Stonehouse’s biography of J Gresham Machen, who went through the same thing when he went to Marburg to study and he came into contact with Hermann and the german liberals of those days, and his correspondence with his mother was very significant in keeping him with just losing his mind.

Ligon Duncan – At that point I thought this would be some kind of hot topic. I had read some Barr in seminary, mostly semantics of biblical language and other things like that, in which, hopefully he is going after some bad stuff, but, I decided that when that book came out that I needed to read everything that Barr had ever written because of the potential influence on scholars. I was doing patristics at Edinburgh and so this wasn’t something that was part of my reading for work, it was just something I needed to do on the side and so I did. It was the most soul killing 6 months that I have ever spent. It was very disturbing. And several things helped me: One is a professor who had already thought through all of these issues. I went to another professor, and as we sat down he said, „You need to know, I have walked through all of these issues long ago and I’m happy to walk with you through them now. That was an enormous intellectual and theological resource to me. But then, it was the reality of Christ and the Gospel and the lives of believers that didn’t even know that they were ministering to me because that person could not be the way he or she is if there wasn’t a Holy Spirit indwelling Christ in us. I was also reading Ned Stonehouse’s biography of J Gresham Machen, who went through the same thing when he went to Marburg to study and he came into contact with Hermann and the german liberals of those days, and his correspondence with his mother was very significant in keeping him with just losing his mind.- Al Mohler – One other thing that was very informative to me was listening to people preach and seeing the distinction in the midst of a huge controversy with some people saying, „I believe in the inerrancy of Scripture and other people saying, „I believe almost the same thing, I just think the words aren’t necessary, etc., etc.” When one got up and said, „This is the word of God”, read the text and preached the text and the other read the text and said, „Let’s find what’s good in here”. And they didn’t necessarily put it that way, but you could tell that is what they were doing homiletically. Here is an accountability to every word of the text. The text speaks because when the text speaks, God speaks. And on the other hand, people saying, „You know, there’s good stuff here, let’s go find it”.

- Peter Williams – I went through a time of significant doubt when I was around 21 , 22. Mark (Dever) was in town at the time, in Cambridge, a great help and the Lord brought me through those, having to work through a lot of that. I certainly looked at liberalism and secular approaches to the Bible, from the inside, within my heart and really, there is nothing there, there’s nothing that has the explanatory power, the comprehensive work that the Gospel, the work in your life and even, also, I think on a historical level there are some amazing things about the Bible. If I can just mention one: Historical level: Go back 400 years to someone like James Ussher (or 350) calculating the dates of Kings of ancient Israel, or Kings of Assyria. That was before archaeology had begun, before the language of the Assyrians had even been deciphered (that’s been in the last 200 years) and he gets the dates of Tiglas Pileser within one year of what now people believe it to be, based on the Bible and he’s not got Hebrew manuscripts any earlier than 11th century AD. and he’s getting reliable information from 1800 years earlier. You can document that. It’s not widely appreciated, but he gets the year 728 and we think it’s 727. It’s pretty remarkable, that sort of level of agreement. It is one of the most amazing stories to me, of historical accurate information being transmitted.

- John Piper – ends with prayer that faith would increase in this generation.

Related articles

- Jesus Christ on the infallibility of Scripture

- John Piper – Why we believe the Bible (5 videos)

- John Piper – How Are the Synoptics “Without Error”?

- Who wrote the Gospels? Are there good reasons to attribute their authorship to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John?

- Does archaeology support the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke)? Part I

- Does archaeology support the Synoptic Gospels Part II

- Good advice on how to deal with Bible difficulties

- Betrayed with a Kiss – Eric Ludy

- Apologetics PAGE

NEWER ARTICLES

Related articles

- The question of the historical Adam and why evangelicals are capitulating on this

- Infallibility vs. Inerrancy of the Bible (Essential Reading)

- Sean Eppers – Why Inerrancy Matters

- What Is Inerrancy? (William Lane Craig)

- Why do we call the Bible inerrant? Carl Trueman

- Inerrancy is Supported Biblically: The Relationship Between the Nature of God and Scripture – Carl Trueman and G. K. Beale

- Michael Horton Is The Doctrine of Inerrancy Defensible?

How do you make sense of contradictions in the Bible? Peter Williams at USC

09 sept. 2013 Un comentariu

in Apologetics, Word of God Etichete:Bible, biblical contradictions, Christianity, God, Internal consistency of the Bible, New Testament, Peter Williams, Religion and Spirituality, USC, Veritas Forum

Cambridge scholar Peter Williams answers USC’s toughest questions about the Bible at The Veritas Forum. Moderated by Dead Sea Scroll expert Bruce Zuckerman.

In this clip, Williams and Zuckerman share their perspectives on how to deal with contradictions in the Bible. Williams suggests that many such cases are deliberate contradictions to draw out important meanings, and that he hasn’t found any unreconcilable statements. Zuckerman suggests that the writers were more concerned with the message and less than the details. http://www.veritas.org/talks VIDEO by The Veritas Forum (Photo below credit onthewarningtrack.podbean.com)

From the video:

„The Bible is full of contradictions,” is a phrase that gets thrown around a lot. How do you understand biblical contradictions as a scholar and how do you understand them as a professing Christian?

Peter Williams:

The way I see things is a contradiction is not necessarily a bad thing, the way Dickens begins ‘A Tale of Two Cities’- ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….’ At which point, you might close the book, or you might struggle on for a few more pages. But the point is that simply using code which is opposite, and someone asks me, „Do you believe this?” And I say, „Yes and no.” Of course my yes is a qualified yes, and my no is a qualified no. But, I have packaged them as a formal contradiction. Now, sometimes bible writers will actually use contradictions quite deliberately.

The way I see things is a contradiction is not necessarily a bad thing, the way Dickens begins ‘A Tale of Two Cities’- ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….’ At which point, you might close the book, or you might struggle on for a few more pages. But the point is that simply using code which is opposite, and someone asks me, „Do you believe this?” And I say, „Yes and no.” Of course my yes is a qualified yes, and my no is a qualified no. But, I have packaged them as a formal contradiction. Now, sometimes bible writers will actually use contradictions quite deliberately.

John’s Gospel has its famous passage: ‘For God so loved the world’. John’s epistle has a passage that says: ‘Do not love the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in Him.’ In other words, telling you not to love the world. But, of course you have to think a little it further about what it means by world, and what it means by love. And John’s Gospel is actually full of these sorts of these things, where it says, „The Son didn’t come into the world to judge it, and in another place it will say ‘for judgment I came into the world.’ And they’re in the same Gospel, sitting alongside each other.

You can find in 1 Samuel 15 where it says that God does not change His mind, he’s not like a man to change His mind, and yet He does change His mind. And it’s all there in the same passage. You can find in 2 Kings 17 a passage that talks about ‘they worshipped God’ and ‘they didn’t worship God’ and then ‘they did worship God’. In other words, you’ve got A B A. Both of those 2 Old Testament passages that I mentioned, where you have a statement contradicting the statements on the two sides, and I think these are things deliberately put there by the authors.

Now, there, I think one of the things that makes us use contradictions less often is that since Aristotle taught us to use technical vocabulary, we like to use one term with one sense. And we don’t like the idea of using one term with multiple senses. That means ancient authors were not constrained in that same way. Now, people might be prepared to accept, when they read John’s Gospel that John has an overall intention when he uses these contradictions. In other words, he’s making you think a little bit further. What happens, though, when they find one thing in one writer and another thing in another writer, and they say, „Well, there’s no way I can fit those together.” Now, the way I would understand things is that things are written in the Bible as such, that there are different authors at the human level, but a single author at the divine level. I can’t prove that, but it seems to me a rational thing. So, I don’t find this sort of contradictions in the Bible which are utterly irreconcilable at any level. In other words, I don’t find them in the Bible something that says Jesus was born in Egypt and Jesus was born in Judea.

I come to the text believing that it speaks truth. I don’t think it has to speak truth according to our conventions, our interest in precision. It can quote in completely different ways than us, because after all speech marks (punctuation ?) were only invented in the last few centuries, so there are all sort of conventions which make it different. But, I think… and this is where we need to have a discussion on this issue, that I think there is an overall coherence within Bible writers, even that come from some pretty different perspectives. I’m happy with tension.

…..

When scholars claim that they found these 2 very different strands which are being combined by some editor at some stage, that is essentially a scholarly reconstruction, all we have is a final text, and the final text is where we start from and and we try to explain how the final text arose as it did. And so, if we have 2 passages alongside each other that seem to us to be different, well, someone put them together and thought that they could fit together. And so, I want to understand that someone’s mind, and I think that very intelligent people can waste a lot of effort dealing with hypothetical sources, and I’m not sure that’s a very fruitful thing.

Evidence from a non christian text that christians were worshipping Jesus as God – Cambridge scholar Peter Williams at University of Chicago

11 dec. 2012 Comentarii închise la Evidence from a non christian text that christians were worshipping Jesus as God – Cambridge scholar Peter Williams at University of Chicago

in Apologetics, Christ, Jesus Christ, New Testament, Resurrection, Salvation, Trinity, Word of God Etichete:Christian, Christianity, Jesus, Jesus Christ, Judaism, Peter Williams, University of Chicago, Veritas Forum

Dr. Peter Williams is currently Warden, Tyndale House, Cambridge

Affiliated Lecturer, University of Cambridge

Honorary Senior Lecturer in Biblical Studies at the University of Aberdeen

Scholarly activities:

- Chair of the International Greek New Testament Project

- Member of the Translation Committee of the English Standard Version of the Bible

Current research includes:

- The early history of translation with particular focus on translation of the Bible

- Textual criticism

At The Veritas Forum at the University of Chicago, Cambridge scholar Peter Williams lists some of the extra-biblical historical evidence for Christianity. He discusses Pliny the Younger’s letter to Trajan about the early Christians as evidence of the beliefs of the early church which worshipped Jesus Christ as God. This – combined with Judaism’s fundamental monotheism – is early evidence that Jesus Christ was quickly given stature as divine and not simply gradually exalted over time. Published on Dec 10, 2012 by VeritasForum

Is there evidence for Jesus outside the Bible? (6 min)

Full library available AD FREE at http://www.veritas.org/talks.

Over the past two decades, The Veritas Forum has been hosting vibrant discussions on life’s hardest questions and engaging the world’s leading colleges and universities with Christian perspectives and the relevance of Jesus. Learn more athttp://www.veritas.org, with upcoming events and over 600 pieces of media on topics including science, philosophy, music, business, medicine, and more!

Here is a lecture Dr. Peter Williams gave from The Lanier Library Lecture Series titled New Evidences the Gospels were Based on Eyewitness Accounts by Dr Peter Williams given March 5, 2011 by fleetwd1

New Evidences the Gospels were Based

on Eyewitness Accounts (54 min)

T4G – Inerrancy: Did God Really Say…? Mark Dever, John Piper, Al Mohler, Ligon Duncan, Dr Simon Gathercole (Cambridge, England), Peter Williams (Warden at Tyndale House)

18 iun. 2012 14 comentarii

in Apologetics, Jesus Christ, Word of God Etichete:Al Mohler, Bible, Biblical inerrancy, Christ and the Bible, Did God really say?, Dr Simon Gathercole (Cambridge England), Francis A Schaeffer, Fuller Theological Seminary, Fundamentalism and the word of God, He is there and He is not silent, inerrancy, J Gresham Machen, J.I.Packer, Jesus, John D. Woodbridge, John Piper, John Wenham, Ligon Duncan, Mark Dever, Ned B Stonehouse, New Testament, Peter Enns, Peter Williams, Scripture and Truth, Together for the Gospel, Together for the Gospel 2012

An essential, highly interesting affirmation by the panel of the belief on biblical inerrancy from the Together for the Gospel Conference 2012, led by Mark Dever, Pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington D.C. Besides the great panel discussion, there are also a few book recommendations (linked to Amazon, just click on title or photo) and lots of links to search peripheral issues as they relate to the inerrancy debate. This page will be added to the (permanent) apologetics page.

An essential, highly interesting affirmation by the panel of the belief on biblical inerrancy from the Together for the Gospel Conference 2012, led by Mark Dever, Pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington D.C. Besides the great panel discussion, there are also a few book recommendations (linked to Amazon, just click on title or photo) and lots of links to search peripheral issues as they relate to the inerrancy debate. This page will be added to the (permanent) apologetics page.

photo from T4G website – http://t4g.org/resources/photos/

- We affirm that the sole (final) authority for the Church is the Bible, verbally inspired, inerrant, infallible and totally sufficient and trustworthy. We deny that the Bible is a mere witness to the divine revelation or that any portion of Scripture is marked by error or by effects of human sinfulness.

- We affirm that the authority and the sufficiently of Scripture extends to the entire Bible and that therefore the Bible is our final authority for all doctrine and practice. We deny that any portion of the Bible should be used in an effort to deny the truthfulness or trustworthiness of any other portion. We further deny any effort to identify a canon within the canon or for example to set the words of Jesus against the words of Paul.

- We affirm that truth ever remains a central issue for the Church and that the Church must resist the allure of pragmatism and post modern conceptions of truths as substitutes for obedience to the comprehensive truth claims of Scripture. We deny that truth is merely a product of social construction or that the truth of the Gospel can be expressed or grounded in anything less than total confidence in the veracity of the Bible, the historicity of the biblical events and the ability of language to convey understandable truth in sentence form. We further deny that the church can establish its ministry on a foundation of pragmatism, current marketing techniques or contemporary cultural fashions.

Is inerrancy something new? Short answer „NO!”

Minute 4 – Dever addresses the charge that „inerrancy” is a „new thing” or just a „reformation doctrine?”.

John Piper responds:.In 1971 Fuller Theological Seminary took the Word out. I read what was happening in Germany. It blew me away. I did not see it coming. So it may have been there, but the teachers that I loved and had influenced me most didn’t talk that way and didn’t give me indication that it would be going that way. I was never able to make any sense out of the distinctions between infallible and inerrant.

John Piper responds:.In 1971 Fuller Theological Seminary took the Word out. I read what was happening in Germany. It blew me away. I did not see it coming. So it may have been there, but the teachers that I loved and had influenced me most didn’t talk that way and didn’t give me indication that it would be going that way. I was never able to make any sense out of the distinctions between infallible and inerrant. - Dr Simon Gathercole – teaches New Testament at Cambridge, in England. One of the clearest figures to express a doctrine of inerrancy was St. Augustine and it came up for him in conversation with the Manichaeans where he made it very clear that there were no contradictions in Scripture , that if you do find what looks like a mistake in Scripture, it is either a result of a problem with the translation, a problem in the text, a particular manuscript or scribal error or that you have misunderstood it. So Augustine is an example of someone who was very clear on inerrancy.

- Ligon Duncan – there is a consistent witness across Christian history to the Bible’s sole, final authority and its inspiration and inerrancy.

Peter Williams – (undergraduate studies at Cambridge) „I believe it is fully authoritative, inerrant, inspired by God’ I think I’d want to add more words, I want to say: It’s basically clear, it’s sufficient, it’s historical. People can take a word like „inerrant” and leech it (by saying) – „I agree with the notion that Scripture is entirely true, but then they try and weaken it in other ways and I think that’s happening particularly because a lot of people, at least in this country are signing an inerrancy statement for their paycheck (which sometimes happens; they redefine inerrancy). There are many reasons to believe in inerrancy, but I think when you believe in verbal inspiration (i.e.) that God gave words and you believe in God’s trustworthiness, that He has a true character and you want to have a relationship with God, then it is inescapable logically to come to a view of Scriptural inerrancy. If you believe that God has given words, I don’t see how you can break that and say, „Well, He gives words and they are sometimes full of errors”, without actually questioning God’s trustworthiness Himself.

Peter Williams – (undergraduate studies at Cambridge) „I believe it is fully authoritative, inerrant, inspired by God’ I think I’d want to add more words, I want to say: It’s basically clear, it’s sufficient, it’s historical. People can take a word like „inerrant” and leech it (by saying) – „I agree with the notion that Scripture is entirely true, but then they try and weaken it in other ways and I think that’s happening particularly because a lot of people, at least in this country are signing an inerrancy statement for their paycheck (which sometimes happens; they redefine inerrancy). There are many reasons to believe in inerrancy, but I think when you believe in verbal inspiration (i.e.) that God gave words and you believe in God’s trustworthiness, that He has a true character and you want to have a relationship with God, then it is inescapable logically to come to a view of Scriptural inerrancy. If you believe that God has given words, I don’t see how you can break that and say, „Well, He gives words and they are sometimes full of errors”, without actually questioning God’s trustworthiness Himself.

The 3 roots/trajectories on how inerrancy is denied

Al Mohler (11 min mark) Why wouldn’t anyone believe in this? (This question) leads to a principle of interpreting church history, which often surprises people when you first hear it, and that is that „heresy precedes orthodoxy„. That doesn’t mean that the false precedes the true. It does mean that the codification, or confession of the faith is often in the face of, is a response to heresy or that which is sub biblical or sub orthodox. So, in 325 AD you have a statement made by the Council of Nicaea, that wasn’t necessary until Arius denied that the father and the Son are of the same substance. And when it comes to inerrancy, the first thing is that this is God’s word, God is totally true, so all the attributes of Scripture seem to come, and yet Augustine has to respond to the Manichaeans and we have to respond to contemporary denials of the total truthfulness of Scripture. I think there are 3 roots, or 3 trajectories in which that comes:

Al Mohler (11 min mark) Why wouldn’t anyone believe in this? (This question) leads to a principle of interpreting church history, which often surprises people when you first hear it, and that is that „heresy precedes orthodoxy„. That doesn’t mean that the false precedes the true. It does mean that the codification, or confession of the faith is often in the face of, is a response to heresy or that which is sub biblical or sub orthodox. So, in 325 AD you have a statement made by the Council of Nicaea, that wasn’t necessary until Arius denied that the father and the Son are of the same substance. And when it comes to inerrancy, the first thing is that this is God’s word, God is totally true, so all the attributes of Scripture seem to come, and yet Augustine has to respond to the Manichaeans and we have to respond to contemporary denials of the total truthfulness of Scripture. I think there are 3 roots, or 3 trajectories in which that comes:

- The first is ideological and this is basically the external critique of biblical inerrancy. It comes from new atheists, of course if you don’t believe in God, you don’t believe there could possibly be a word of God; if you don’t believe in supernatural revelation as a possibility, or even recently, if you don’t believe in words as units of meaning; that are capable of conveying truth, there are various rules of philosophy and literary interpretation that have lost all confidence in words. They have to use words to explain how little confidence they have in them any longer; it’s part of the whole conundrum, but nevertheless, it is an ideological assault and so a good bit of what you will read simply says: „Inerrancy is an impossibility” and it will move on. But, it is not the major issue of our concern, there are two other trajectories.

- Another trajectory is apologetic. This is where you have evangelicals who say: This is an embarrassment. To claim inerrancy is to over claim the text, it is an impediment to our intellectual credibility and so you have people who would pose to be within the evangelical movement who will say, as Kenton Sparks in a recent book said, „This is the intellectual doom,” to paraphrase him, because it makes us continually defend the truthfulness of every passage in a text and that is leading modern people to have huge intellectual obstacles to receiving the main message in the text, which is the Gospel of Jesus Christ. So you have various forms of this kind of apologetic argument; it’s the same argument as people who come along and say you can’t talk about the Bible’s teaching on sexuality; that’s presenting too much of an obstacle for contemporary people to come to Christ. Ot, you can’t deny the theory of evolution, it’s metanarrative because that creates too much of an impediment for people to come to Christ. And so, you have websites today and people arguing that inerrancy is just an obstacle, it’s a theological construct that’s doing more damage than good.

- The third trajectory, or the third root you can look at this is moral, in which case you have people say that if we’re committed to total truthfulness of Scripture, then we’re committed to text which reveal God as acting in immoral ways; God’s people sanctioning immoral acts, and what you have is people who will say, „Look, we have the capacity as human beings to judge God, and thus we’re gonna go to the conquest of Canaan or we’re gonna go to the way God deals with any individual in either Testament of the canon and say that that’s immoral. If you’re gonna try and impose a human standard of morality, like the late atheist, Christopher Hitchens, if you read the Bible honestly you’re gonna find texts that are gonna cause you all kinds of difficulty and by the way, one of the things Christopher Hitchens did very well for us was to say, „He can understand theists who believe in the inerrancy of Scripture and he can understand atheists who don’t believe it’s possible, what he didn’t understand were people who tried to pose in the middle.

Dr Simon Gathercole – The central plank for me in the doctrine of inerrancy, and that is that it was Jesus’ view of Scripture and I think the 2 other points that were mentioned are really significant. The sort of dogmatic logic of what Scripture says, God says and therefore because of the character of God, Scripture is without error. Also, it’s the continuous testimony of the Church. I would recommend everyone read John Woodbridge’s book Biblical Authority: A Critique of the Rogers/McKim Proposal even though the debate is now different, but there’s a lot to learn there. But, if you just look at the way Jesus treats Scripture, what He says about Scripture, „Your word is truth”, „Scripture cannot be broken”, the way He refers to Adam, the way He refers to Elijah and Elisha, all the figures of the Old Testament, the way He responds to Satan: „It’s written, and every word is proceeding from the mouth of God.” That has to be the real cornerstone for our doctrine of inerrancy and it means that it’s an imperative of discipleship for us, that it’s a matter of following Jesus. (Also recommends „Christ and the Bible” by John Wenham)

Dr Simon Gathercole – The central plank for me in the doctrine of inerrancy, and that is that it was Jesus’ view of Scripture and I think the 2 other points that were mentioned are really significant. The sort of dogmatic logic of what Scripture says, God says and therefore because of the character of God, Scripture is without error. Also, it’s the continuous testimony of the Church. I would recommend everyone read John Woodbridge’s book Biblical Authority: A Critique of the Rogers/McKim Proposal even though the debate is now different, but there’s a lot to learn there. But, if you just look at the way Jesus treats Scripture, what He says about Scripture, „Your word is truth”, „Scripture cannot be broken”, the way He refers to Adam, the way He refers to Elijah and Elisha, all the figures of the Old Testament, the way He responds to Satan: „It’s written, and every word is proceeding from the mouth of God.” That has to be the real cornerstone for our doctrine of inerrancy and it means that it’s an imperative of discipleship for us, that it’s a matter of following Jesus. (Also recommends „Christ and the Bible” by John Wenham)- Peter Williams – If heresy precedes orthodoxy then I think that apologetics precedes heresy, as in most heresy begins as apologetics movement. And, I say that as someone who is involved in apologetics and likes it. Liberal theology is an attempt to rescue Christianity from deep embarrassment and that’s how a lot of these things begin and those of us that are involved in apologetics need to be quite careful about that, because it can lead to error. The way people get seduced sometime into abandoning Scriptural authority is when they become persuaded that, that thing which adheres most to their dreams and their aspirations and start to believe „that more people will come to Christ if I just water this down somewhat”. Sometime people become persuaded in theological education that they are being more faithful to the text if they read it in a way that is contrary to another text. When people are being brought up in a Chirstian context, to value the authority of the Bible, it appeals and they become persuaded that the most honest reading of the text is to read it so it contradicts to another one.

- Al Mohler – Liberal theology is a succession of rescue attempts for the reputation of Christianity and to just give an example of what Peter is talking about: You have Rudolph Bultmann, who in one of his books says people who use electric lights don’t believe in a supernatural universe. So, in other words, if you’re gonna reach modern people we’re gonna have to bring christianity into intellectual credibility with the modern world. A lot of the things you see being claimed right now are as old as the heretics that the church fathers faced and certainly in terms of protestant liberalism and what the church has faced in over 100 years.

Ligon Duncan – Another example in modern liberalism is Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher. Schleiermacher was offended by the doctrine of the penal substitutionary atonement of Christ and the uniqueness of Christ. And he looked out at Germany and he said: German intellectuals are rejecting Christianity in droves, they’re impacted by the enlightenment and the message of Christianity must change if we are going to be able to capture this generation for christianity. It wasn’t as if he was sitting around inventing to destroy christianity, but in fact he did that with apologetic missionary motives in reaching his culture and so liberalism’s fundamental premise is that the message must change if christianity is going to survive and effectively engage the culture.

Ligon Duncan – Another example in modern liberalism is Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher. Schleiermacher was offended by the doctrine of the penal substitutionary atonement of Christ and the uniqueness of Christ. And he looked out at Germany and he said: German intellectuals are rejecting Christianity in droves, they’re impacted by the enlightenment and the message of Christianity must change if we are going to be able to capture this generation for christianity. It wasn’t as if he was sitting around inventing to destroy christianity, but in fact he did that with apologetic missionary motives in reaching his culture and so liberalism’s fundamental premise is that the message must change if christianity is going to survive and effectively engage the culture.- Peter Williams -It’s going right back to Marcion in the second century. Marcion is deeply embarrassed by the Old Testament, by the Jewishness of Jesus. He, as an apologist thinks that he can commend christianity far better by ditching those things. So, that’s why becoming an apologist, led straight to the heresy.

John Piper (minute 20 mark) Mark Dever asks why JP concluded that inerrancy was true: There are layers to that like- My momma told me it was true. That’s one layer. „..remember those from whom you’ve learned the faith” (2 Timothy 3:14), that’s an argument in the Bible. Second layer would be: God made me see it. That’s the deepest layer and I do believe I couldn’t believe the Bible is untrue, if I tried because I am just taken by Him, for it. I believe that’s the deepest reason. You can’t persuade anybody with that and so, up above those layers are the layers of experience, of encounter with the text and I think that at one level the Bible, as C.S.Lewis said: „You believe in it as you believe in the sun, not only because you see it, but you see everything else by it”. I asked my professor in Germany one time, „Why do you believe the Bible? And he said: Because it makes sense out of the world for me. Year after year, after year you live in the book and you deal with the world and it brings coherence to evil and good and sorrow and loss. And there’s one other level I would mention: Liar, lunatic, Lord argument in the Gospels works for me in Paul: Liar, lunatic or faithful apostle because I think I know Paul better than I know anybody in the Bible. Luke wrote most quantitatively, but he’s writing narrative. But with Paul, if you read these 13 letters hundreds of times, you know this man. Either he’s stupid, I mean insane, or liar, or a very wise, deep, credible, thoughtful person. So, when I put Paul against any liberal scholar in any German university that I ever met, they don’t even come close. So, I have never, frankly, been tested very much by the devil or whoever to say, „This wise, liberal, offering his arguments…” I read Paul and I say, „I don’t think so”. This man is extraordinary, he’s smart, he’s rational. He’s been in the 3rd, 7th heaven and he is careful about what he is saying. So, that whole argument „Liar, lunatic, Lord – works for me with Jesus and it works powerfully for me for Paul and moreover once you’ve got Paul speaking, self authenticating, irresistible, world view shaping truth, then as you move out from Jesus and Paul, the others just start to shine with confirming evidences. Just a few ayers, there are others. Dever prompts John to give one more. JP: Why are you married after 43 years? How do you endure losses? really, where does your strength come from? You will know the truth and the truth will set you free. Free from pornography and free from divorce, free from depressions that just undo you. How do you find your way into marriage over and over and out of depression and away form the internet? How does that happen? It happens by the power of this incredible book. Dever: For people who haven’t had time to accumulate all those layers, anything you would tell them to read? Piper: Back when the inerrancy council was red hot „Scripture and truth” edited by Grudem and

John Piper (minute 20 mark) Mark Dever asks why JP concluded that inerrancy was true: There are layers to that like- My momma told me it was true. That’s one layer. „..remember those from whom you’ve learned the faith” (2 Timothy 3:14), that’s an argument in the Bible. Second layer would be: God made me see it. That’s the deepest layer and I do believe I couldn’t believe the Bible is untrue, if I tried because I am just taken by Him, for it. I believe that’s the deepest reason. You can’t persuade anybody with that and so, up above those layers are the layers of experience, of encounter with the text and I think that at one level the Bible, as C.S.Lewis said: „You believe in it as you believe in the sun, not only because you see it, but you see everything else by it”. I asked my professor in Germany one time, „Why do you believe the Bible? And he said: Because it makes sense out of the world for me. Year after year, after year you live in the book and you deal with the world and it brings coherence to evil and good and sorrow and loss. And there’s one other level I would mention: Liar, lunatic, Lord argument in the Gospels works for me in Paul: Liar, lunatic or faithful apostle because I think I know Paul better than I know anybody in the Bible. Luke wrote most quantitatively, but he’s writing narrative. But with Paul, if you read these 13 letters hundreds of times, you know this man. Either he’s stupid, I mean insane, or liar, or a very wise, deep, credible, thoughtful person. So, when I put Paul against any liberal scholar in any German university that I ever met, they don’t even come close. So, I have never, frankly, been tested very much by the devil or whoever to say, „This wise, liberal, offering his arguments…” I read Paul and I say, „I don’t think so”. This man is extraordinary, he’s smart, he’s rational. He’s been in the 3rd, 7th heaven and he is careful about what he is saying. So, that whole argument „Liar, lunatic, Lord – works for me with Jesus and it works powerfully for me for Paul and moreover once you’ve got Paul speaking, self authenticating, irresistible, world view shaping truth, then as you move out from Jesus and Paul, the others just start to shine with confirming evidences. Just a few ayers, there are others. Dever prompts John to give one more. JP: Why are you married after 43 years? How do you endure losses? really, where does your strength come from? You will know the truth and the truth will set you free. Free from pornography and free from divorce, free from depressions that just undo you. How do you find your way into marriage over and over and out of depression and away form the internet? How does that happen? It happens by the power of this incredible book. Dever: For people who haven’t had time to accumulate all those layers, anything you would tell them to read? Piper: Back when the inerrancy council was red hot „Scripture and truth” edited by Grudem andMark Dever recommends J. I. Packer’s „Fundamentalism and the Word of God”.

- Al Mohler – The problem is how few of our confessional statements are clear on this in the first place. So one of our evangelical liabilities is that too much has been assumed under an article of Scripture without specifying language, with inerrancy being one of those necessary attributes of Scripture confirmed. You do find people today, some lamentably who are trying to claim that you can still use the word, while basically eviscerating it, emptying it of meaning. So you have historical denials, in particular, you have someone who says that a text… and „The Chicago Statement on Inerrancy” makes it very clear, our affirmations and denials are actually patterned after the International Council of Biblical Inerrancy, which was itself patterned after previous statements in which there were not only affirmations, but clear denials. So, when you look to that statement, you’ll see that there’s the version of what inerrancy means and that means „This is not true”. So, you have clear denials. One of the affirmations is: Scripture has different forms of literature, but the denial is that you can legitimately dehistoricize an historical text. So, in other words, everything in Scripture reveals, including every historical claim is true. You find some people saying: „Well, you can affirm the truthfulness of the text without the historicity of the text. You can’t do that. You have people who are now using genre criticism, various forms to say: This is a type of literature. My favorite of these lamentable arguments is the one that says: This is the kind of text to which the issue of inerrancy does not apply. In other words: I don’t like it. But, what they mean is: I am not making a truth claim. If I am not making a truth claim… that’s ridiculous, but you find these kinds of nuances going on. You also find very clear, points of friction. So, let’s give an example of points of friction: Do we have to believe in the historicity of the first eleven chapters of the book of Genesis? What Pete said about apologetics, that puts us over, against a dominant, intellectual system that establishes what is called credibility in the secular academy. Those evangelicals who feel intellectually accountable to that, are trying to say, „There has to be some other way then, of dealing with Genesis 1 through 11 and that’s where you have now the ultimate friction point, with coming, for instance, the historical Adam and an historical fall and now you’re finding people who are trying to say, „Okay, there is no historical claim in Genesis 1 through 3, but I still believe in an historical Adam because I am just going to pull him out of the air and pop him down and say, „I still believe in an historical Adam (but) I am not going to root it in the historical nature of the text, but I need him because Paul believed in him. And then, you have people who have websites today, someone like Peter Enns, who used to teach at an institution which required inerrancy, but no longer teaches there, who says, „Clearly, Paul did believe in inerrancy, but, Paul was wrong”. And so, now you not only have the denial of inerrancy of the historicity of Genesis 1 through 3, you have Paul now, in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 being said, „Well now, inerrancy for him means ‘he was speaking truthfully, as inspired by God, but limited to the world view that was accessible and available to him at the time’. That is not what Jesus believed about Scripture. That is not what the church must believe about Scripture. I never came close to not believing in the inerrancy of Scripture. I came close to believing that there could be other legitimate ways of describing the total authority and truthfulness of the text and especially in context of fierce denominational controversy, I thought there must be room for finding it somewhere else and some people even mentioned here were correctives. For example J.I. Packer’s Fundamentals of God, was the bomb that landed in the playground. That little experiment just doesn’t happen; you take that out, it simply won’t work. At about the time that you (Mark Dever) and I really became friends, we were looking at how you came from an evangelical background where those issues have been discussed for 20 years before they did explode in the Southern Baptist Convention. My denomination had to learn this lesson a little bit late and at great cost.

- Mark Dever– leaving the denominational stuff aside, you (Mohler) as a Christian, you found an intuitive, like John is talking about, an intuitive faith in Scripture.