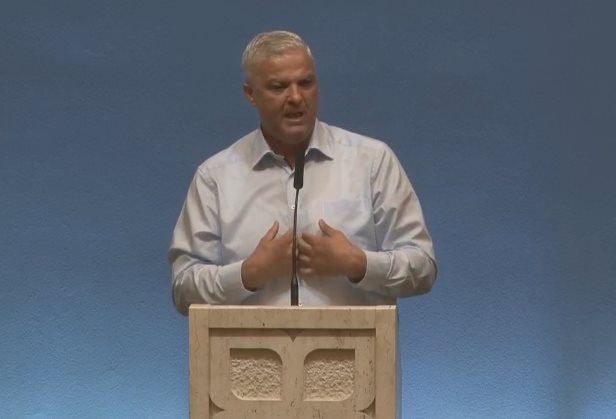

Cate ceva despre mine, pentru cei care nu ma cunoasteti. Sunt credincios Domnului din tinerete, la 17 ani am facut legamantul cu Domnul, ca urmare a unei lucrari de trezire spirituala in Oradea, in vremea fratelui Liviu Olah, pastor atunci la Oradea. Am facut inginerie, dar la 30 de ani, ca Domnul Isus, m-a chemat Domnul in lucrare. Am lasat ingineria si am intrat pastor in perioada comunista, 1987. Am inceput studii teologice, mi-am luat toate gradele acestea care erau necesare. Tocmai atunci, la Oradea, a inceput Universitatea Emanuel de astazi si am fost prins in echipa de profesori. Am ajuns sa studies, sa devin profesor, practic din 1981 sunt profesor de teologie. Am fost 10 ani profesor la Oradea, 11 ani la Institutul Teologic Penticostal din Bucuresti si de cativa ani sunt acum la Facultatea Teologica Baptista din Universitatea Bucuresti. Locuiesc in Timisoara, impreuna cu a doua mea sotie, Tatiana. Prima mea sotie a murit intr-un accident de masina in anul 2005, la doua saptamani dupa ce am sarbatorit 25 de ani de casnicie. Cu ea am avut 6 copii. Unul dintre copii, un baiat de 21 de ani a murit in 2009. M-am casatorit dupa 2 ani de vaduvie cu Tatiana. Ne-am stabilit in Timisoara acum; predau cursuri modulare la nivel de masterat, dar sunt invitat la toate scolile posibile din Romania, exceptand una de la Oradea. In rest, peste tot, usa-i deschisa si slujesc cu bucurie peste tot. Salutari de la toti profesorii de la toate aceste scoli de la bisericile care le-am vizitat in ultimul timp. In ultimii 5 ani de zile am primit de la Domnul o lucrare noua: sa intaresc bisericile, sa le intaresc cu darul meu de dascal / invatator. Si asta am facut.

Cate ceva despre mine, pentru cei care nu ma cunoasteti. Sunt credincios Domnului din tinerete, la 17 ani am facut legamantul cu Domnul, ca urmare a unei lucrari de trezire spirituala in Oradea, in vremea fratelui Liviu Olah, pastor atunci la Oradea. Am facut inginerie, dar la 30 de ani, ca Domnul Isus, m-a chemat Domnul in lucrare. Am lasat ingineria si am intrat pastor in perioada comunista, 1987. Am inceput studii teologice, mi-am luat toate gradele acestea care erau necesare. Tocmai atunci, la Oradea, a inceput Universitatea Emanuel de astazi si am fost prins in echipa de profesori. Am ajuns sa studies, sa devin profesor, practic din 1981 sunt profesor de teologie. Am fost 10 ani profesor la Oradea, 11 ani la Institutul Teologic Penticostal din Bucuresti si de cativa ani sunt acum la Facultatea Teologica Baptista din Universitatea Bucuresti. Locuiesc in Timisoara, impreuna cu a doua mea sotie, Tatiana. Prima mea sotie a murit intr-un accident de masina in anul 2005, la doua saptamani dupa ce am sarbatorit 25 de ani de casnicie. Cu ea am avut 6 copii. Unul dintre copii, un baiat de 21 de ani a murit in 2009. M-am casatorit dupa 2 ani de vaduvie cu Tatiana. Ne-am stabilit in Timisoara acum; predau cursuri modulare la nivel de masterat, dar sunt invitat la toate scolile posibile din Romania, exceptand una de la Oradea. In rest, peste tot, usa-i deschisa si slujesc cu bucurie peste tot. Salutari de la toti profesorii de la toate aceste scoli de la bisericile care le-am vizitat in ultimul timp. In ultimii 5 ani de zile am primit de la Domnul o lucrare noua: sa intaresc bisericile, sa le intaresc cu darul meu de dascal / invatator. Si asta am facut.

Dupa ce am trecut prin aceste mari incercari in viata, nu mai puteam face anumite lucrari pe care le-am facut inainte. Si Dumnezeu mi-a aratat ca aceasta e noua lucrare, noua traiectorie a mea si am acceptat-o si sunt implinit in ceea ce fac. De aceea m-ati invitat, pentru ca… nu stiu exact de ce, dar Domnul a deschis usa. Nu trebuia sa fiu acum aici, trebuia sa fiu in Republica Moldova, dar s-a inchis acolo usa, s-a deschis la voi. A fost providential. Ma bucur sa fiu cu voi aici. N-am auzit multe despre voi dinainte, dar mi-ati produs, pana acuma, o impresie calda deosebita.

Imi place sportul, am jucat fotbal- mijlocas, fratilor (cand eram cu vreo 30 kg mai putin). Am jucat handbal vreo 3 ani, acuma joc sah. E o gluma. Imi plac cartile. Va spun hobi-urile mele, ca sa stiti ca am o parte umana, sa n-o auziti de la altii. Ce auziti la altii nu-i corect.

Photo credit si comanda aici – http://www.logos.ro/

Imi plac cartile, mai ales teologice, evident. „Preaching & Preachers”, cartea lui Martyn Lloyd-Jones- s-a tradus in Limba Romana deja? Da, s-a tradus acum.

Apropos, de Martyn Lloyd-Jones, a fost primul autor englez. A fost medic al Casei Roiale din Anglia, a parasit medicina pentru pastorala. Pe urma a devenit predicator la Westminster Chapel si a fost unul dintre cei mai mari predicatori ai secolului XX. Minunat predicator. Aceasta carte , despre predicare, cred ca e tradusa in Limba Romana. Pute-ti verifica. E una dintre cele mai bune. Am citit-o cand eram mai tanar decat tine, Adi. (Nu am gasit cartea- daca cineva o gaseste, va rog frumos sa ne anuntati si adaugam linkul) M-a hranit foarte mult aceasta carte si cartea lui John Stott despre predicare- Puterea Predicarii. E tradusa la Editura Logos din Cluj.

- Citeste aici o recenzie pentru PREDICAREA si PREDICATORII de Ghita Mocan – http://jurnalulpleroma.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/2001-02-dec-gheorghe-mocan.pdf

- Carti de autorul Martyn Lloyd-Jones traduse in Limba Romana – http://www.kerigma.ro/

- Puterea Predicarii de John Stott aici – http://www.logos.ro/

Photo credit si comanda aici – http://www.clcromania.ro

Aceste doua carti sunt fundamentale, pentru ca, daca tot am inceput- John Stott a fost anglican. A murit de curand, nu s-a casatorit niciodata. Un om extrem de inteligent, Doctor in Teologie si profesor, dar mai mult s-a dedicat lucrarii cu studentii. Toate cartile pe care el le scria aveau trecere, se vindeau foarte bine. Esentialul Crestinismului a fost cea mai vanduta carte, Zeci de milioane de exemplare s-au vandut in lume, si alte carti. Toti banii primiti din drepturile de autor de la aceste edituri,el le punea intr-un fond special, se numeste Langham Partnership care sprijinea educatia in tarile mai putin dezvoltate- Africa, Europa de Rasarit. Asa, foarte multi Romani, talentati, buni, au ajuns sa studieze masterate, doctorate, in Vest din cauza acestui fond de bani de la John Stott. L-am cunoscut personal. Am fost chiar la el in casa, in birou. Era pasionat de pasari. A scris si doua carti din perspectiva crestina despre pasari. Da, fratilor, se poate si asa. Insa cartea despre predicare merita citita de toti.

In paralel, a trait Lloyd-Jones, mai in varsta de John Stott. El era, nu anglican, atat cat era Metodist Calvinist. O combinatie imposibila doctrinar. Dar, in el s-a putut. Foarte bun predicator, s-au certat. Cei doi s-au certat. Da, s-au certat si ei. Prin anii ’60 – ’66, parca, a avut loc o disputa si iata care era disputa. Evanghelicii din Biserica Anglicana nu erau de acord cu ce facea ‘High Anglican Church’, cum se spune- Biserica care avea legatura cu statul, care avea liturghie, care nu prea era evanghelica. O mare parte, poate o treime din biserici, din pastorii anglicani erau evanghelici. Credeau in necesitatea nasterii din nou, in sfanta Scriptura ca autoritate finala si Lloyd-Jones, la Congresul Evanghelicilor, a propus iesirea evanghelicilor din Biserica Angliei.

Citeste despre aceste conferinte in intregime aici (L. Engleza) –

- (1)Addresses by Dr Lloyd-Jones on Christian Unity at The Third Assembly of the World Council of Churches at New Delhi, December 1962

- (2) Addresses by Dr Lloyd-Jones on Christian Unity at The Third Assembly of the World Council of Churches at New Delhi, December 1962

- (3) Martyn Lloyd-Jones – The Third Assembly of the World Council of Churches at New Delhi from those that were there (Lloyd-Jones vs. John Stott)

- (4) Martyn Lloyd-Jones – The Third Assembly of the World Council of Churches at New Delhi – What the Newspapers and Books Reported 18th October 1966

- (5) Martyn Lloyd-Jones – On Schism (5th February 1961)

- (6) Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones at the Evangelical Alliance 1966 by Geoff Thomas

- (7) Dr. Martyn Lloyd-Jones – British Evangelical Alliance 1966 – Conclusion (Nov 1996)

- Martyn Lloyd Jones – Preacher (Biography and Online book by John Peters)

Argumentul lui (Lloyd-Jones) a fost ca nu poti sta intr-o biserica care se compromite. Inca de atunci erau semne ca Biserica Angliei va fii de acord cu hirotonisirea femeilor. Si iata ca asa a fost. Plus, au inceput sa accepte si homosexualii, [au] preoti si episcopi homosexuali. La asta s-a ajuns. De atunci, Lloyd-Jones a vazut ca directia bisericii nu era buna si a zis: „Iesim si formam o alta denominatie evanghelica.” John Stott era de partea cealalta. Era mai tanar, credea ca biserica se poate innoi din interior. El a spus: „Daca noi plecam din Biserica Angliei, nu mai este speranta pentru ei. Ramanem.” S-a supus la vot. Au votat mai multi cu John Stott- cu ideea lui, nu cu el. Ideea, sa ramana in Biserica Anglicana si sa incerce sa o schimbe din interior. NU AU REUSIT. Lloyd-Jones s-a separat; n-a reusit nici el prea multe. Erau prea putini sa formeze o alta denominatie. Si asta a fost disputa.

Ce faci cand biserica in care tu esti nu merge in directie buna, din punct de vedere doctrinar?

Nu-i vorba ca iti place sau nu de un lider. Doctrinar slabea, erau semnele compromisului. Unul a spus: „Iesim.” Celalalt a zis: „Ramanem ca s-o schimbam.” Celalalt a zis: „Iesim, nu ne compromitem.” Ce ai fii ales?

Stii cum s-au format Baptistii? Baptistii au iesit din Biserica Anglicana, pentru ca nu erau de acord cu compromisul Bisericii Anglicane si aveau alta doctrina. Deja botezul adultilor era profilat, separarea Bisericii de Stat. Astea erau doctrine de baza. Preotia tuturor credinciosilor, fara o baza ierarhica. Stiti cum s-au format penticostalii? O, vreau sa va spun ceva. In fruntea primilor penticostali in miscarea Church of God (1901) si apoi Assemblies of God (1906) din America (in anii astia s-au format), in fruntea Bisericii Church of God au fost 2 metodisti. Si in fruntea Bisericii Assemblies of God a fost un pastor Baptist. Deci, Penticostalii s-au format iesind din Metodisti si din Baptisti pentru ca aveau alta doctrina. Nu a fost alt motiv. Nu au fost dati afara. Baptistii au ramas pana au fost alungati. Au trebuit sa fuga la Amsterdam si asa s-a format Biserica. Sa stiti, mentalitatile acestea se simt in istorie, daca te uiti. Ele sunt formate deja. Nu trebuie mult.

Sa zicem, uitati care e diferenta de gandire. Sa luam un om de afaceri Baptist. Esueaza, nu-i iese ceva. Ce face un om de afaceri Baptist cand nu reuseste? Intra in el insusi ai spune: „Eu sunt de vina. Eu am gresit ceva. Eu, eu, eu…” Ce face un om de afaceri penticostal, daca nu reuseste? „Diavolul e de vina.” Doua atitudini diferite. Mentalitati diferite. Unul introspectie, celalalt nu are asa mari probleme cu … Cauta. Ah, atacul celui rau. Astea se pastreaza in istorie, sa stiti. Acuma, sunt si amestecuri. La Crestini dupa Evanghelie nu ma pot pronunta.

Dar, vedeti? Suntem pusi in astfel de situatii. Ne tot intrebam, ca deja incep prezentarea mea despre liderul crestin in diaspora. De ce se impart asa de des bisericile in diaspora? (1-16)

Dr. Jones: Yes. This is where we’ve got to start, with man as he is today. And my quarrel is, with the general outlook of today is this: that they begin to talk about treatment before they establish a true diagnosis. Now, I can’t help putting it like this, you see; it’s a very poor doctor who medicates symptoms and isn’t aware of the disease that is producing the symptoms. Well, to me, the disease is this fallen sinful nature of man. And because that is true, none of your medication of the symptoms is going to deal with the problem. And I maintain that this is what history is teaching us, that with all our advantages today, the problem is as great as ever.

Dr. Jones: Yes. This is where we’ve got to start, with man as he is today. And my quarrel is, with the general outlook of today is this: that they begin to talk about treatment before they establish a true diagnosis. Now, I can’t help putting it like this, you see; it’s a very poor doctor who medicates symptoms and isn’t aware of the disease that is producing the symptoms. Well, to me, the disease is this fallen sinful nature of man. And because that is true, none of your medication of the symptoms is going to deal with the problem. And I maintain that this is what history is teaching us, that with all our advantages today, the problem is as great as ever. And there appeared to them tongues as of fire distributing themselves, and they rested on each one of them. (Acts 2:3)

And there appeared to them tongues as of fire distributing themselves, and they rested on each one of them. (Acts 2:3) What does this mean? Fire in the Bible is symbolic of three things — purity, power, and passion. Isaiah is purified by altar coals. Jesus’ baptism of the Spirit and fire promises the coming power of God. And God’s messengers are a flaming fire, filled with passion to take the gospel to the nations. By all means, we ought to reject semi-Pelagianism and what comes from it; but we must also reject the notion that all we need is the sufficiency of the Scripture. We need both the Scripture and the Spirit. We need to take up the sword of the Spirit which is the Word of God (Eph. 6:17) but we must also pray with all perseverance and petition in the Spirit for all the saints, that the Word may go forth with boldness (Eph. 6:18-20). How do we get there? We must have Holy Ghost fire. We must have the unction of the Spirit (1 John 2:20). There is only one way, and that is earnest prayer and supplication, pouring out our hearts to God in repentance, asking for the Holy Spirit (Luke 11:13), seeking his presence and power until we get it (James 4:8). If you are a preacher then make this your highest priority in ministry. If you support your preacher in prayer, and surely you should do so, then pray that the unction, Holy Ghost fire, will come with fulness in purity of motives, power in preaching, and passion in pursuit of ministry. I know — it looks strange, decidedly uncool in our day when hip and laid back is in — but we ought to go to church and watch our pastor burn with Holy Ghost fire as he stands to proclaim the unsearchable riches of Christ. This is not a casual thing. This is not a ‘maybe you ought to think about it’ proposition. This is life and death (2 Cor. 3-4). Our words are a savour of life unto life or death unto death (2 Cor. 2:15-16).

What does this mean? Fire in the Bible is symbolic of three things — purity, power, and passion. Isaiah is purified by altar coals. Jesus’ baptism of the Spirit and fire promises the coming power of God. And God’s messengers are a flaming fire, filled with passion to take the gospel to the nations. By all means, we ought to reject semi-Pelagianism and what comes from it; but we must also reject the notion that all we need is the sufficiency of the Scripture. We need both the Scripture and the Spirit. We need to take up the sword of the Spirit which is the Word of God (Eph. 6:17) but we must also pray with all perseverance and petition in the Spirit for all the saints, that the Word may go forth with boldness (Eph. 6:18-20). How do we get there? We must have Holy Ghost fire. We must have the unction of the Spirit (1 John 2:20). There is only one way, and that is earnest prayer and supplication, pouring out our hearts to God in repentance, asking for the Holy Spirit (Luke 11:13), seeking his presence and power until we get it (James 4:8). If you are a preacher then make this your highest priority in ministry. If you support your preacher in prayer, and surely you should do so, then pray that the unction, Holy Ghost fire, will come with fulness in purity of motives, power in preaching, and passion in pursuit of ministry. I know — it looks strange, decidedly uncool in our day when hip and laid back is in — but we ought to go to church and watch our pastor burn with Holy Ghost fire as he stands to proclaim the unsearchable riches of Christ. This is not a casual thing. This is not a ‘maybe you ought to think about it’ proposition. This is life and death (2 Cor. 3-4). Our words are a savour of life unto life or death unto death (2 Cor. 2:15-16).

The chairman, John Stott, sensed that many men were being stirred to action and feared that some Anglican clergy might leave their church. Although he had already been given a ten minute slot earlier in the meeting to state his own views, he rose, at the end of the Doctor’s address not to close the meeting, but to counter what had been said. Being a young, impetuous non-conformist at the time, I secretly hoped that

The chairman, John Stott, sensed that many men were being stirred to action and feared that some Anglican clergy might leave their church. Although he had already been given a ten minute slot earlier in the meeting to state his own views, he rose, at the end of the Doctor’s address not to close the meeting, but to counter what had been said. Being a young, impetuous non-conformist at the time, I secretly hoped that